Racing against time at DiviPay

For the last couple years I have been working at DiviPay on building the next generation of expense management software covering everything from expense reimbursement for employees to controlling your budgets and subscription payments to virtual cards. It has been a wild ride so far and has presented many interesting challenges for myself and the team. In this post I will be explaining how we faced into an interesting performance problem and managed to not only solve it but exceed our expectations.

Payment Cards

Payment cards are a wide-spread payment method around the world, you probably have one in your wallet right now in the form of a credit or debit card from your bank. In my role I am often working with virtual payment cards which are a payment method that is very similar to a physical credit/debit card but is only available online. These payment cards present some interesting challenges for an engineering team when viewed from both a security and performance perspective.

Security and Correctness

Traditionally, a payment card is attached to some kind of bank account and besides some fraud rules and restricted merchants the logic for allowing a payment is to check whether there is enough funds available in the account or on the line of credit before approving the payment to go through. This does not need to be the case and in DiviPay’s case, we actually build on top of this logic to allow the cards to respect multiple different limits or rules at one time. This allows us do some interesting things such as having different card numbers per subscription with different maximum amounts but only maintaining one account to fund all the subscriptions. As a trade-off, this means we need to process more logic at the time of payment to achieve these features and make sure each card only approves payments it is supposed to accept.

Performance

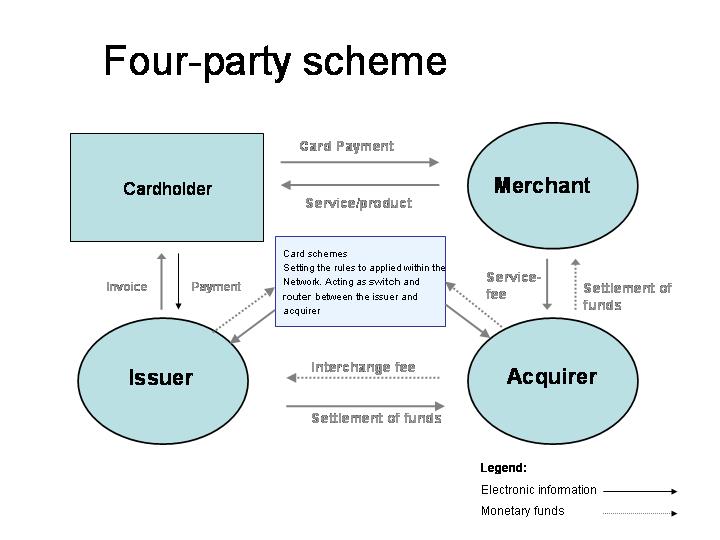

As mentioned above, to build these more complex approval features we need to put more logic between the payment being requested and the approval of the payment. To understand the importance of this we must first understand the four-party card scheme.

The four-party scheme is a type of payment network used to allow card holders to make payments to various merchants. This is the way schemes like Mastercard and Visa work.

In the four-party scheme, there are four different parties (surprising right?):

- Cardholders: This is the person or entity that has is trying to make a payment with a card (physical or virtual).

- Issuer: This is the entity or group of entities that issues the cards to the card holders.

- Acquirer: This is the entity, often a bank, that receives and stores the money from the payment.

- Merchant: This is the merchant that the cardholder is trying to pay.

The benefit of using a four-party scheme is that the merchant and cardholder don’t need to figure out how to exchange funds between each other and can leave the acquirer and issuer to figure out the specifics.

As a payment is made by a cardholder and flows through the scheme from the merchant, through the acquirer and to the issuer and back it may face various checks to decide whether the payment should be successful. At the high level, the entity running the scheme (read Mastercard/Visa) often enforces a maximum threshold for how long this process can take and then each entity in the process must respond within some threshold below this maximum.

In DiviPays case we have a maximum of 3 seconds to respond with whether or not a payment should be accepted or not. Now this seems like a lot but you need to take into account that this is measured by the entity upstream from us so includes things like network latency which can have a significant impact on the total time taken to respond.

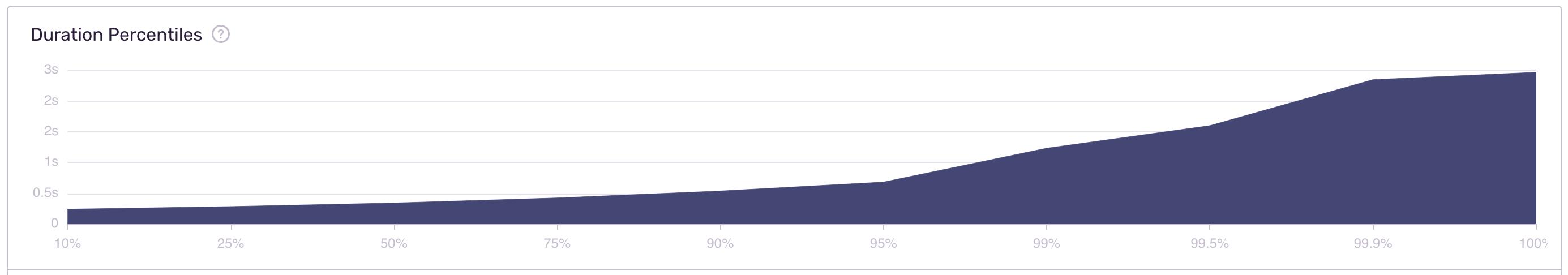

Setting The Bar

We had recently implemented some metrics around our payment approval flows to keep an eye on the percentage of failed payments and we noticed that we were only hitting around a 93% success rate including payments that we had responded to in time but hadn’t reached the upstream issuer in time. To make sure that payment requests are resolved and responded to within 3 seconds we needed to set a target for some time that was realistic but effective, taking into account the network latency that was also contributing to the slowness. In the 7% of payments that failed, we noticed that a large number of them had actually been responded to in our systems in less than 1.5 seconds which meant that there was significant delay in the network every now and then. At lot of this was out of our control however we could control the 1.5 seconds that the payment was in our system. We decided to aim for 2 SLOs being a p99 of payments being under 1.5 seconds and a p95 of under 800ms which would give ample time for the payment to get back through the network.

Finding The Low-hanging Fruit

Having not performance optimized our payment approval at this point there was probably some pretty large changes we could make in the flow to reduce the time it took to process each payment. To find this we did a group code review to find obvious code smells such as querying the database multiple times for the same information or information that wasn’t needed. Once we had completed this process we began profiling the the flows in our beta environments to find any issues we hadn’t caught in code review. As we use Django we were able to do this with some simple middleware like this:

class ProfileMiddleware:

def __init__(self, get_response):

self.get_response = get_response

def __call__(self, request):

pr = cProfile.Profile()

pr.enable()

response = self.get_response(request)

pr.disable()

s = io.StringIO()

sortby = "cumulative"

ps = pstats.Stats(pr, stream=s).sort_stats(sortby)

ps.print_stats()

print(s.getvalue())

return response

Through this process we were able to eliminate a decent amount of computation that was either doing too much work or had remained as legacy code that didn’t need to run anymore. This process got us to around 95% of our p99 target of less than 1.5 seconds but there was still something missing that wasn’t obvious in the cProfile output.

Sentry Performance

I have long been a fan of Sentry for error monitoring in various systems I’ve worked on and when they released an APM tool a few months ago I jumped at the opportunity to try it out. Reasonably quick to set up and released, Sentry Performance samples your incoming requests or whatever you want to call a transaction in your system and provides valuable metrics around them such as p95/99, APDEX scores and the number of users impacted.

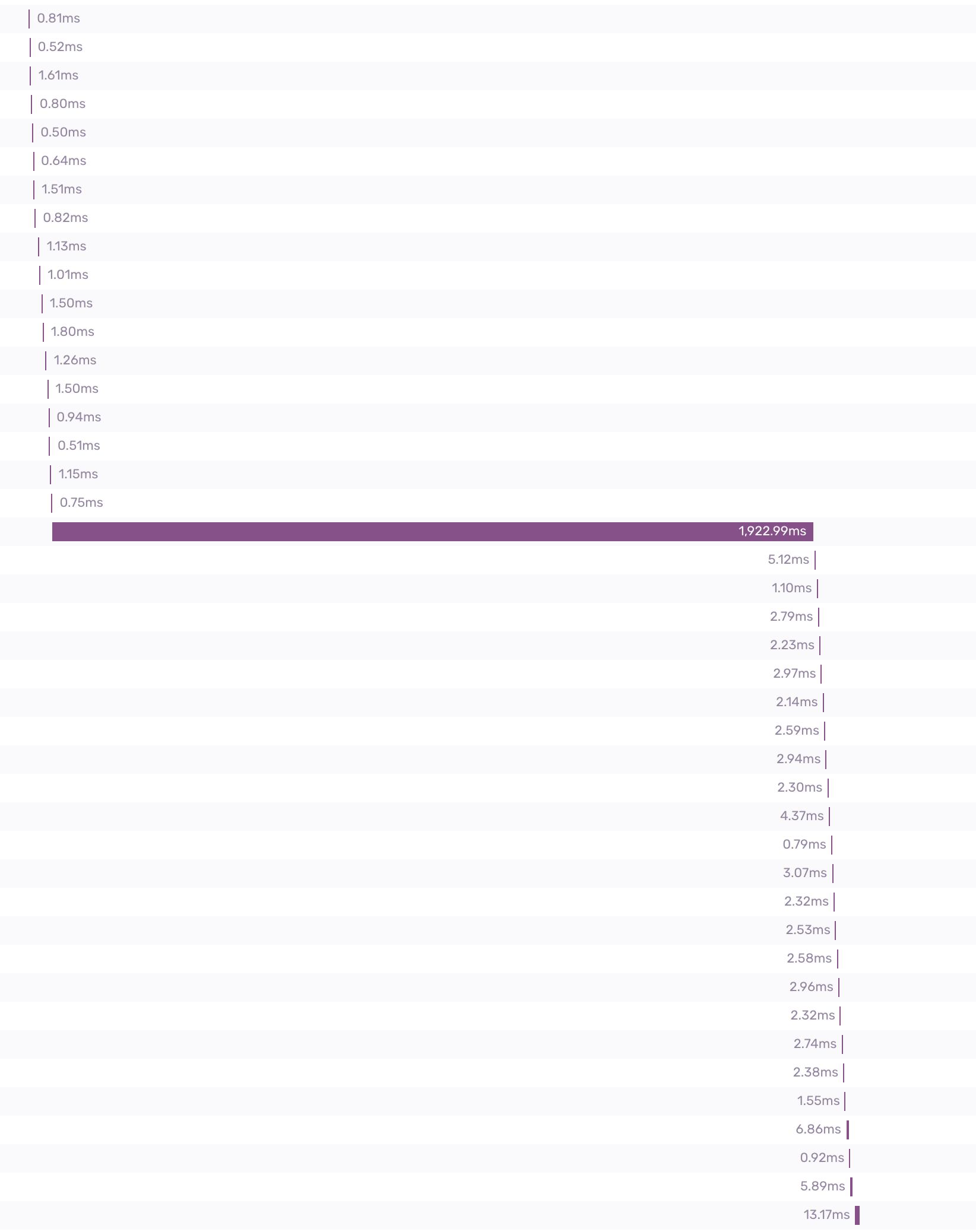

This decision was a game changer for us as it helped us to find the subset of requests in production that was causing the slowness in our system. Below is an example of what we were seeing for some payments, the large bar in the middle was a very slow database query that was doing some joins on some huge tables that wasn’t actually needed.

This visual representation of the bottlenecks made it incredibly easy to find the issues in our code and figure out whether there was a better way to achieve the same result or even question why certain things needed to happen.

Results

While we still have much to do we have now hit our SLOs of a p99 < 1.5 seconds and a p95 < 800ms as shown below. By tackling this problem systematically by measuring the initial baseline and impact and the profiling and monitoring our changes we have been able to deliver our customers a much smoother payments experience and an overall better customer experience.

If you have enjoyed this blog and think you’d like to help solve similar problems in engineering or payments, DiviPay is hiring!