The Sydney Train Carriage Problem

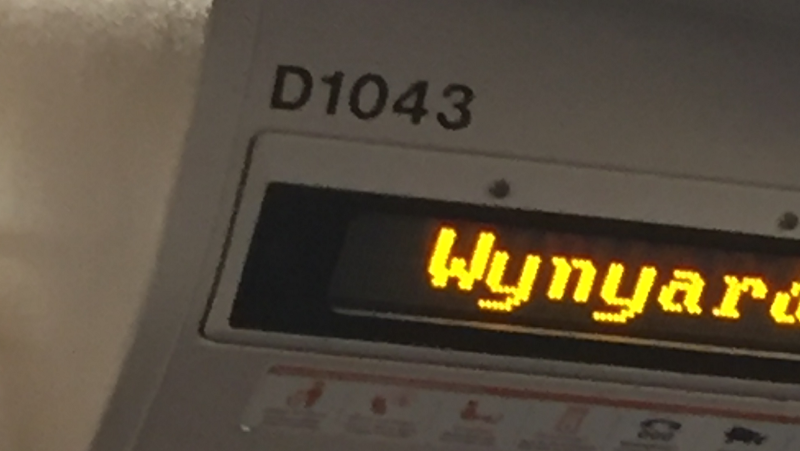

Living in Sydney it is inevitable that I travel via the public transport system, after all the highways are so congested that there is no other option unless you’re in a position to pay exorbitant housing prices, but that’s another story. On the Sydney trains, each carriage has a unique 4 digit number, usually preceded by some letter, printed up on the interior wall. They look like this:

It has been a reoccurring game amongst my friends over the past few years that whenever we are on a train we need to try to make 10 using the carriage number. Furthermore, I believe this game is known amongst many Sydneysiders and hence I decided to write about it. The rules are simple though there are a few variations:

- Using common mathematical operations make 10 using the individual digits from left to right.

- Using common mathematical operations make 10 using the individual digits in any order you like.

For example, the carriage number might be 5432, ignoring the prepended letter. An appropriate solution might be 5 + 4 + 3–2 = 10.

The Hypothesis

My simple hypothesis, and many may concur, is that since I have never met a train carriage number where I haven’t found a solution, I propose all carriage numbers can be arranged to equal 10.

The Method

Thinking about the problem (Are all train carriage numbers solvable?) I found that writing a proof would require some form of mathematics where I could essentially do algebra on operators rather than the numbers they control, being unsure about how to do this I turned to a programmatic approach. Please contact me if you know how to mathematical prove this.

I decided that since there were only 10000 numbers I needed to test, I would just brute force the combinations of operators and see how I went. My code is written in Python3 and is available on GitHub. Please note the code may or may not be polished when you get there.

I had a weak goal of also trying to get as many numbers covered with the minimal number of mathematical operators, so in running my experiments I added new operators after each previous experiment in the hopes of raising the total coverage of numbers. I refer to coverage as the percentage of numbers that had solutions equal to 10.

The Experiments

My first lot of experiments ran through the numbers testing equations of the form ((w O x) O y) O z = 10, where O is just a placeholder for random operators and w, x, y, and z are the digits of the carriage number.

Running this with the operator set {+, -, *, /} yielded a 42.09% coverage, a lot lower than I expected. This led me to think about what kinds of tricks my friends and I had deployed on particularly tricky numbers.

In the second test, I added the floor and ceil operators resulting in a hugely positive increase to 67.94%. My hypothesis was looking a tad more likely. What was I missing though?

Another operator that I had been holding off on adding due to the added complexity was the factorial operator. I only allowed factorial to be calculated on the single atomic digits, not the results of other operators. This led to a dramatic performance decrease, even with cached answers, though it raised the coverage to 87.31% which also raised my hopes of a correct hypothesis.

In another attempt to raise the coverage, I switched to variation 2 of the problem (allowing rearrangements of the number) which led to an increase to 97.18% coverage. This particular variation, which still included factorials on the atomic digits, was very very very slow. I knew that if I was to keep experimenting I would need to speed it up somehow. My first instinct was to run the experiment concurrently. Though this led to a small speedup, each number was taking a second or 2 which meant that the computation was still too slow and heavy for my Macbook Air to handle. I needed a boost, and I found that boost in an AWS EC2 c4.8xlarge.

Only ~3% left uncovered, precisely 282 numbers that I could not find a solution for. I thought it would be worth looking at the numbers that failed and where they fell in the range 0000 to 9999. My suspicion was that a large chunk of them would fall below 1000. Unfortunately, there was only 85 failures, which meant I still had 197 lurking within the remaining 9000 numbers.

Moving onto my next experiment my plan was to run through the full 10000 numbers but also keep a track of the failures so that I could rerun the tests on a much smaller range moving forward. Why didn’t I think of this earlier?

So to begin with I ran the 2nd experiment again (basic ops and floor/ceil), but keeping track of which numbers failed this time around. Since I’m allowing for rearrangements now, we could reduce the set even more since different sequences of numbers are equivalent. I.e 0114 is the same as 4011, 4101, etc. This speeds up the total computation time as we know that if we can solve for 0114 we also solve the other permutations of those digits.

Adding in factorials led managed to reduce this set to the 282 numbers I was looking for. In my final experiment I added the exponentiation as well as allowing the absolute value operator.

The Final Result

After the experiment finished I was left with the following sequences:

These sequences allow for rearrangements, this is how I calculated them:

So, there we have it, 185 numbers cannot (as far as I have calculated) be solved to equate to 10 given the operators: addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, floor, ceil, atomic factorials, exponentiation, and absolute value; allowing rearrangement. As a percentage, there was a 98.15% success rate.

Conclusion and Reflection

Although I was unable to cover all 10000 numbers, I am happy with the results. Furthermore, I suspect that the Sydney trains numbers don’t actually start from 0000 but from 1000 instead (I may be wrong about this). If I’m right about my previous statement, then there were only 121 failures, leading to a success rate of ~98.66%. That list contains theses numbers:

In regards to what I have learnt from this problem, I have learnt to focus more on reducing a problem, in how I only needed to test the failures of the previous experiments.

I have yet to find any particular pattern in the failures that would allow me to recognise a number as unsolvable, if any readers spot anything, I would appreciate you passing it onto me. As for the next steps towards 100%, I would like to see factorials added into the calculation on all elements, not just the initial digits.

I hope I have provided an insight into the Sydney Train Carriage Problem and would love to see any further work on the problem, especially a formal proof of whether or not all of the 10000 numbers are solvable. I imagine if not all number 10000 numbers are solvable then then proof might take the form of a contradiction based around either proving 0000 or 1000 are unsolvable.